X: Sieve

The things we sift, the things we toss.

Good morning. Today is décadi, the 30th of Nivôse, Year CCXXXI. We celebrate le crible, a screen that lets the good stuff fall out.

Nivôse is the hardest month. The French Republican calendar was set up to acknowledge the farming cycles of the year, but when it hit this point after the turning of winter, all that was left were some rickety tools for tossing wheat around and rocks. Lots and lots of rocks.

My neighbor had a rock tumbler when I was growing up, and I was always jealous of that noisy contraption that could take any stone and, after a day or two, turn it into a smooth and colorful wonder (or, most often, a black lump without bumps, but that was still pretty cool). Wearing things down is laborious, and noisy, and violent, even if the end results shine.

Much gentler to shake and sift. Which brings me to gold panning.

We don't get to talk about gold, officially. It's the obvious omission from this month of minerals and stones. This makes sense when you consider what the French revolution was revolting against, which was the gilded legacy of the Sun King and his fat, callous progeny, an aristocracy that had abandoned Paris to construct for themselves a great hall of light, full of mirrors to reflect all the dazzling gold they'd plundered from the labor of French workers and the corpses of French infantry and the frozen fingers of French colonists. To them, gold was a symbol of corruption, greed, and death.

I grew up in Colorado, a state that was, itself, colonized for gold. Before I ever learned of the peoples whose names graced our roads and high schools and cities and counties, the peoples who were slaughtered systematically, I learned of the great gold miners and their wealth.

I learned of the Unsinkable Molly Brown, who survived the Titanic wreck and parlayed her fame and considerable fortune (from mining) into a world-class hotel in downtown Denver. I learned of the vast mines that dotted the highway on the way to ski resorts, and of the streams that once sparkled with golden flakes carried from the deep mysterious bellies of the Rockies. And I learned to pan.

You can't attend a summer camp in Colorado without being given a rusty old cake pan and being told to swish some stream water in it. Usually, they'd also have a practice station seeded with gold-rich dirt in sluice, so we could try our hand at the slow swirling motion needed to rinse away silica particles and leave a few flakes of gold in the crevice of the tin.

If you got good, you could have the finer mesh-bottomed pan that would sift the tiny flakes into a second bottom (to further pan later, if you cared) and see if you could catch a nugget. Nobody ever did. All the nuggets had been picked up and hauled away to build our city on the prairie and paint the massive dome of its capitol.

On a trip to visit my parents, I took my kids to a mine tour in the mountains and had them repeat the experience, standing around a sluice with little pans and hunting for flakes. They were indifferent to the results, even though they each walked away with a dollar or two in flakes (the dirt we toyed with being carefully calibrated to have enough gold to make the $5 experience not feel like a rip-off while still yielding an easy profit). For reasons I still don't understand in words (but get on a gut level), my oldest took her test tube of gold-flecked water and poured it out on the mountain. There's gold in them thar hills again.

So much of life is sifting. Straining our thoughts for something that feels true. Combing the debris from the dog's hair. Squeezing a lemon half over our hands to let the juice slip through the finger cracks and onto the fish while catching the seeds. Every sifting action comes with a decision – do you want the stuff that falls through, or the stuff that stays behind?

The small stuff or the large stuff?

Everything seems to begin as a mixture of both. Large and small come together to make a universe, make a life. Sifting is a human and futile attempt to decouple them, to reduce the entropy of life ... but does the entropy really disappear when we always seem to throw away one half or the other?

Gold panning is a large stuff activity, trying to let the little things falls away and leave only the beautiful, the valuable, the soft, and the delicate. Everything else isn't worth our attention when gold is around.

But the revolutionaries knew. They had been deemed ugly, worthless, hard, and small. They had lived a life with all the gold removed, and they hated it. They hated it to an eventually murderous and mad degree. They had been tossed aside.

How healing, how fitting, then, is the seemingly careless and stupid act of tossing out the vial of gold? It's still there. It hasn't gone anywhere. It's just back where it belongs, mixed in with everything else.

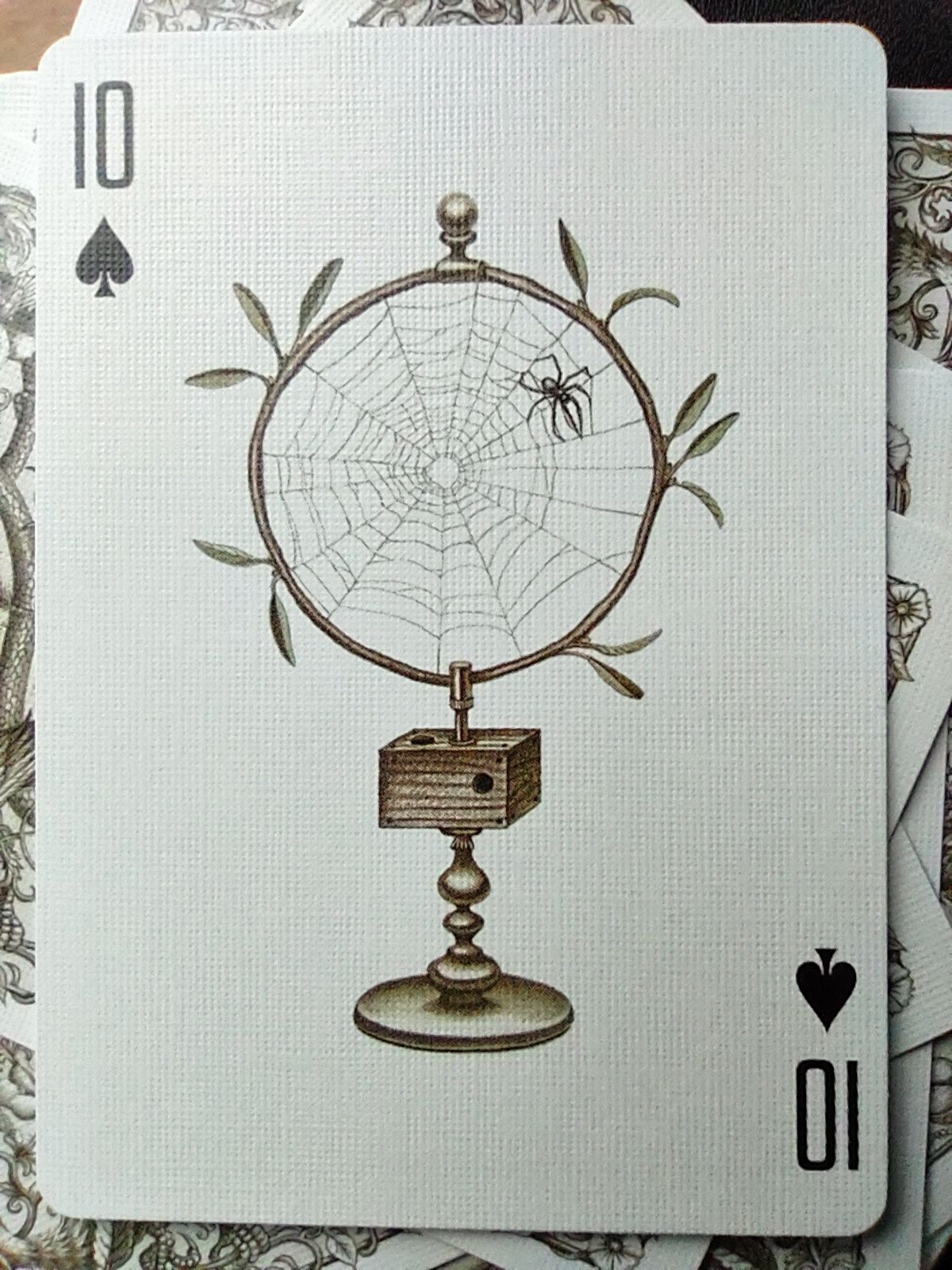

Today's card: 10 of spades

Click for a recap of the story so far...

Naveen is a comic book artist is stoked (9♦) to have lucked into a new freelance gig (8♦) with a major publishing company (6♥) after suffering through a terrible job (3♦) that he hated (3♣). This gig should go fairly well no matter what (8♣), so Naveen shouldn't stress out too much (5♣), but he should really put his whole heart into it (9♦) and try to make a connection with an industry veteran (10♠).

The story ends as I'd hoped it would, with Naveen putting a true masterpiece out into the world, something that feels natural but woven from dreams caught in his subconscious for years. The remarkable run of high-numbered cards spoke clearly (as did the few threes pertaining to the past gig), so this is a high-confidence reading. A note on how I pull these: after shuffling, I cut the deck then count off the number of cards corresponding to the day before flipping, to avoid any bias toward bent or frayed cards. These are truly random draws. I'm so excited to see what the spread of Pluviôse have in store!

Something fun: Boston College sieve chant (60sec)

College hockey fans are brutal to goalies, and every major program has its own version of a "sieve" chant to hurl at an opposing netminder who has just allowed a goal. My alma mater, Colorado College, just had to be different and yell "colander," but the idea is still the same: this kid lets things through. To make sure the player gets the metaphor, some variation of "you suck" is always included.