X: Lock

The good intent and bad failure of caisson locks.

Good morning. Today is décadi, the 20th of Thermidor, Year CCXXXI. We celebrate l'écluse, a device for getting shipments around on a river.

Prior to railroads (so, for most of human history), the way to move a ton of heavy goods all at once was on the water. People sometimes assume that cities were always built near rivers for drinking water needs, but fresh water for daily use can be found underground. The purpose of building near rivers was that they were the highway system of yore, and if you wanted any stuff to come or go from your settlement, you wanted to be next to that highway.

A big, navigable river was every founding villager's dream, but rivers have a way of being finicky in regards to elevation. You may have a nice, fat, wide ribbon of water with easy portage along your town, but a mile or two away a cliffside will send that river cascading down as a treacherous waterfall into a rock-filled pool – not exactly great for sending boats to the ocean for trade. And don't even start on how boats coming from the ocean are going to climb that waterfall.

That's why, despite the tremendous amount of engineering and construction prowess involved, locks and canals are a lot older than you might assume. The oldest known ones were built in China more than a thousand years ago. Give humanity a serious enough problem, and we'll find a solution that's centuries ahead of its time.

These locks basically work as a pair of dams. For a boat going downriver, the lower dam is closed while the upper dam stays open, allowing the segment in the gap to fill with water until it's even with the upper reach. The boat floats in, the dam closes behind it, then the dam in front has an underwater opening – called a paddle – winched open to drain the water out. The boat chills out while it's slowly lowered to the bottom reach's elevation, then the lower dam is opened and the boat goes on its way, waterfall avoided.

Boats going up would do the same thing, but in reverse, gradually lifting up with the water being filled from the upper reach of the river while the dam behind them stays closed to hold them (and the water) in the lock.

This has worked for a millennium and is still the way canals do business today, though most of them have motorized paddles rather than burly men at an iron wheel. The only hitch in traditional locks is that you need to be able to count on that upper reach of the river having a steady flow of water. The whole thing counts on water filling up the lock. Like I said, rivers have a way of being finicky.

This became a more acute problem at the onset of the Industrial Revolution, when factories started demanding coal for their infernal machines, but those same coal-driven machines hadn't yet been perfected for making engines and therefore trains. How to get the coal from the mountains – where most rivers are seasonal and still small – to the population centers on the navigable rivers below? This was the central problem at the time of the French Revolution, and probably one reason why locks show up here – an ancient tool that a lot of brilliant engineers were working on improving.

One such engineer was Robert Weldon, who was hoping to solve the issue of getting coal from Somerset down the Avon River in England. Not only was the river smaller than your usual shipping lane, there were numerous mills and farms along it with ironclad water rights who weren't too keen on a series of locks being built that would whoosh all the water away from them all day. So Weldon invented the elevator.

Well, he called it the caisson lock, but basically it was a large elevator shaft cut into the rock and sealed, then filled with water. Inside this watery chamber there was a watertight box with just enough liquid in it to keep a boat afloat. The first gate would open, the boat would float in, then the gate would close and the boat would be lowered in its elevator car through the chamber of water until it reached the bottom, when another gate would open. The brilliance here was that the outer and inner chambers were always full of the same-ish amount of water, so there was no disruption to the water levels upstream.

We've all used elevators, so this is pretty sound technology. However, I'd venture to guess that none of us used elevators that floated underwater. There's an obvious safety reason for this, one that was compounded by the technology available to Weldon when he built this in VII (1799).

The first test leaked. They patched up the inner box and tried again, and the next three tests were successful. Excited about this proof-of-concept, Weldon rounded up some investors – including the Crown Prince who would later be King George IV – and took them on a ride. Well, the future king stayed ashore. Which actually everyone could have. All anyone needed to see was boat-go-in, boat-come-out, but Weldon was enthusiastic about showing these wealthy people the inside of his pitch-dark box.

The boat went in and began its descent through the lock's enormous water chamber, sealed in against millions of pounds of water pressure. Then, the inner box hit a stone protruding from the outer box's wall, and got stuck. The problem here was that the water-proofing after the first failed test was so thorough that it had also air-proofed the joint. The passengers inside were stuck for hours and rapidly losing oxygen.

Somehow (disappointingly no contemporary sources get into how) the box was unjammed and the passengers (and boat) released at the bottom of the lock safely. But funding would be a bit harder to get after that. No caisson lock was ever built. By the time the materials and engineering necessary to make this safe had arrived, so had railroads, and big complicated river engineering issues were left to big complicated oceanic shipping routes, not little local coal routes. It took coal-powered engines to get coal down from the hills to make more coal-powered engines. Water wanted nothing to do with that.

By the way, before we go blaming the builder for not hammering in all the stones super well, it should be pointed out that the device engineered its own demise. Those millions of pounds of water pressure were squeezing around this box, which – in order to let the boat safely get in and out – basically took up the entire width of the water chamber. You can imagine the pressure the water "flowing" around its sides would attain, and this is what quickly deformed the walls before the lock had even been used five times.

While caisson locks were never built as Weldon designed them, the creativity involved did spur forward some innovations in canal locks that eventually led to improvements in important shipping places like the Erie and Suez and Panama Canals. So these were studied for more than just laughs. But for a chuckle, imagine being a crown prince sitting on a hillside, astride your horse, watching several of your wealthiest citizens going into a chamber full of water and then ... not coming out. That's a reaction video I'd pay to see.

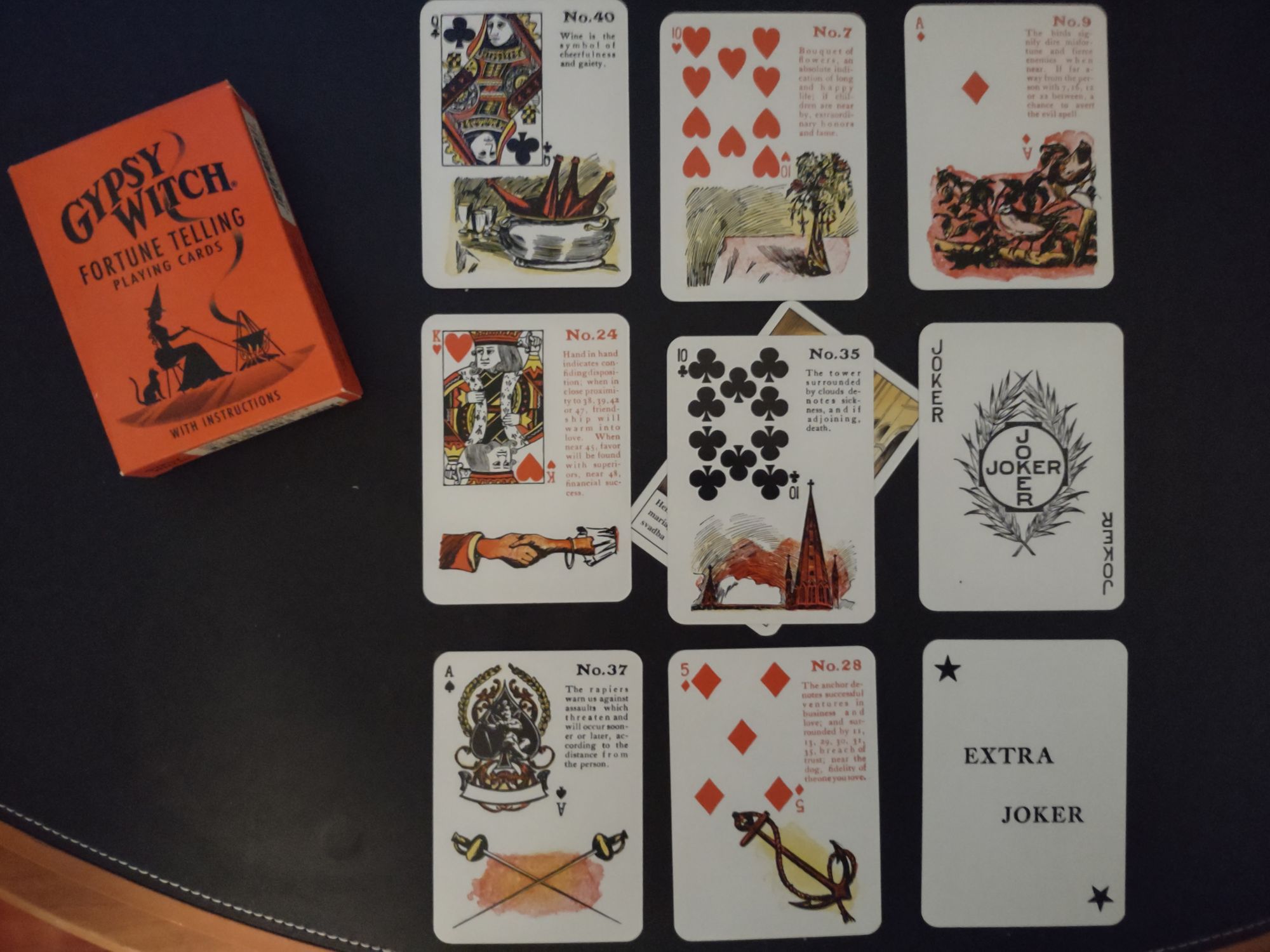

Today's card: Joker!

Ah, this deck has decided to close out our reading with a wink. Both Jokers sit just where they should, in the uncertain future, but in this case, that uncertainty rests mainly within our hearts. The Tower in the center never had any evil confirmed by the reading – rebuffed, really, if anything – so perhaps we just need to peer inwards to see where our troubled mind is originating. Back to the old Celtic cross starting tomorrow!