X: Grafter

A mountain village that invented the factory.

Good morning. Today is décadi, the 30th of Germinal, Year CCXXXI. We celebrate le greffoir, a tool for making fruit happen.

There's a small town in the central mountains of France that makes almost all the knives for the country, and has done so for 600 years.

Thiers is situated on a cliff's edge next to the rushing mountain river of La Durolle. It exists largely because of a Roman road that terminated there, creating a path for trading goods, but the town itself is not a Roman town. It wasn't founded until a castle and church were thrown up there in the 10th century. The area has no sandstone or iron. Its only asset was the river. That was enough for some anonymous person, likely returning from a crusade with knowledge of knife making, to start an industry there that revolutionized mass manufacture centuries before the industrial revolution.

Knife making certainly began in the 15th century, as there were already a few dozen residents of Thiers listing that as their profession on the tax rolls, a number that would swell to more than 200 in the following century when Thiers solidified itself as the knife capital of France. That was more than a quarter of the small commune's population at the time.

In those days, artisans worked in a studio system, employing a handful of people to manufacture goods from raw material to finished product. But if Thiers – which again, had no raw materials handy for either the knife blades or the grindstones needed to shape them – operated in this way, there would have been an absurd number of studios for such a small settlement all competing for virtually no buyers.

What developed instead was a town-sized factory with groups of men specializing in one particular part of the knife making process. In a sense, the town itself produced the knives, as shops organized for each part of the manufacturing chain to make the next step down the line their primary customer. This isn't unusual in today's world of supply chain-based industrial factories, but it was unheard of in medieval France, and gave Thiers the ability to flood the region with quality knives and corner the market.

There were traders who traveled afield to source the iron and sandstone, lumber mills that exclusively harvested wood appropriate for knife handles, wood turners who made the handles, smelters who rendered the iron, and artisans who assembled the various pieces. But the real competitive strength of Thiers was in its "yellow bellies," or blade carvers.

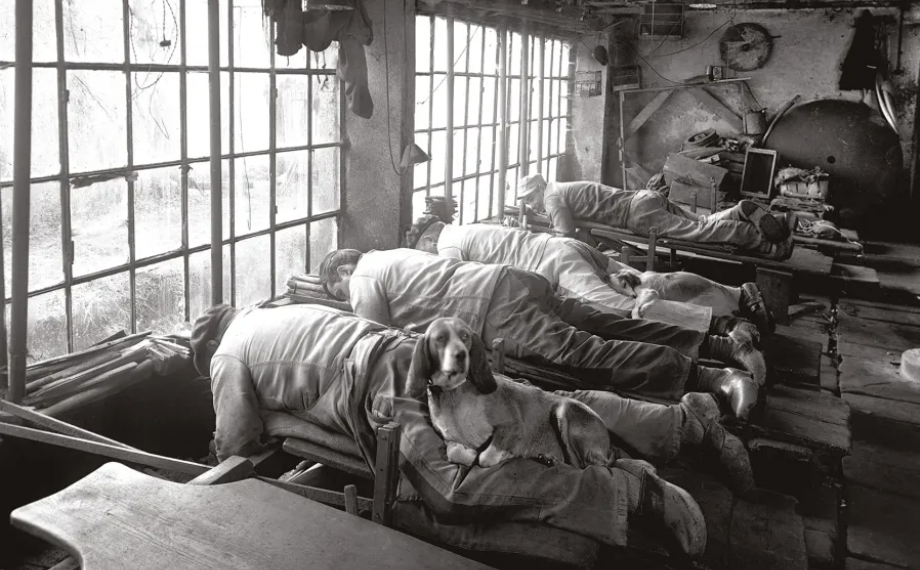

A vast blade carving building known as L'Enfer (Hell) was situated at the top of a cascading waterfall, with great grindstones turned by the rush of the water. In order to use these grindstones, the carvers would lay down on planks overhanging the waterfall and dangle their arms, working in a face-down position all day over the whirring grindstones.

The conditions were brutal. Laying on one's stomach on a flat board of wood for 10 to 12 hours every day – no days off – led to circulation problems and bruising (the likely source of the yellowbelly nickname), and their perch atop of the cold mountain waterfall was chilly year-round. It was common practice for each worker to purchase a dog that would lay on their legs all day to keep them warm and provide a safe counterbalance on the plank.

The noise was literally deafening, and there was always a chance that a grindstone would develop a crack and then explode, the centrifugal force so strong that the fragments of the heavy stone would literally fling the cutler all the way to the ceiling, usually resulting in death.

Most of the knives manufactured at Thiers were everyday multipurpose cutlery. A knife was a common person's eating and working utensil, serving as everything from an awl to a carving blade to a small crowbar. Many of the knives were pocket knives – initially without any spring, just folding on carefully measured friction – meant to be carried around the fields of French wine country, where they would come in handy for grafting and pruning.

While the manufacturing plants have changed dramatically and are now electrically driven instead of hydrodynamically, Thiers has kept its reputation – and its market share of 70 to 80 percent of all French blades – all the way to today. For centuries, the knife makers of Thiers were content to create designs that were named after other regions: Spanish navajas, Louguille pocket knives, and so on. Since CCII (1994), there is now also a "La Thiers" style of knife that is a long, curved folding blade, although it's less of a specific design than a set of quality controls:

- the maker must have at least 5 years of experience as a cutler and be in the Thiers cutlery guild,

- the design has to be accepted by the guild,

- the knife has to be marked with a "T" logo and say “Le Thiers par…” including the name of the manufacturer on the blade,

- the manufacturing must be entirely done within Thiers,

- and the raw materials used must be approved by the guild for quality control.

These knifes run about $200, but would be the only knife you'll ever need for rough outdoor use. If you were thinking of cobbling together a pomato plant, acquiring a good, sharp knife is the right way to begin.

Today's card: 6 of diamonds

No matter what the fears were for this project, things will at the very least turn out well financially. It's not a huge windfall, but in the overall context of how well things are going in our personal life, it's enough to enable a treat on the town, and that may be where a new friendship is found. Thanks for following along during an unusual suite of Germinal readings. Tomorrow, we inaugurate my favorite month, Floréal!